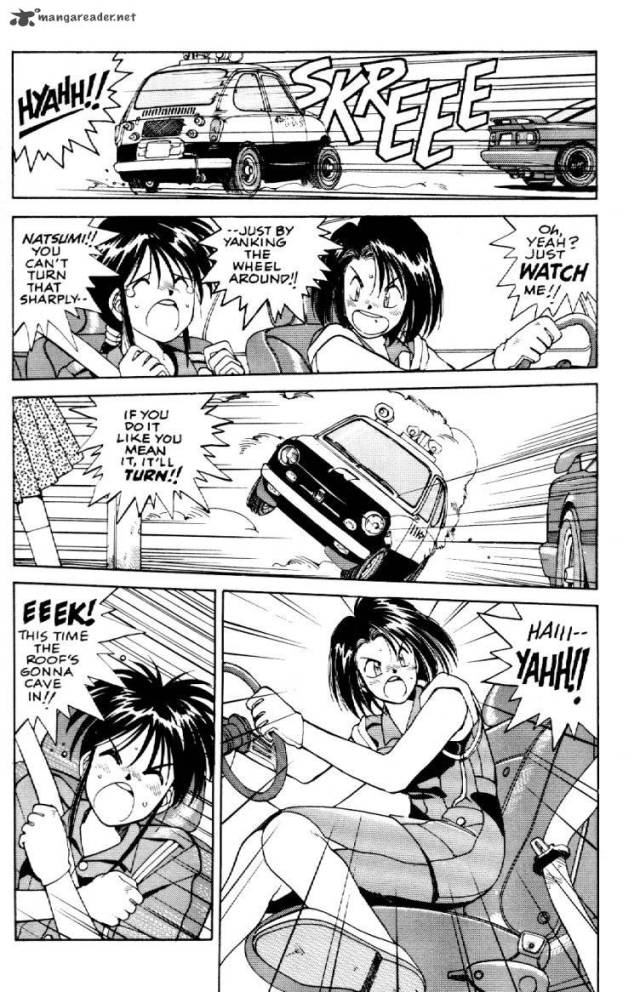

About one year ago, I discovered You’re Under Arrest, a very amusing series by Kousuke Fujishima who is also famed for Ah! My Goddess! It excels in showing spectacular car chases, amusing plots, likeable characters, comedy, and even has a very believable and nice–though frustrating at times–romance for those of you who care about that facet of storytelling. (Okay, I’ll admit that I’m sometimes a sucker for that too.) This TV series began with a four episode OVA, which became popular enough to warrant a series. However, I consider the OVAs to be the weakest episodes of the first season, to which the OVA was attached, with the exception of the OVAs having better animation quality. But, the comedy and the plots of You’re Under Arrest only improved from there.

On the other hand, the second season started pretty strong. Saori’s entering into Bokuto Station with a ton of youthful rigor made for some splendid comedy as our heroes and their comrades tried to restrain her high ideals. Saori is eventually relegated to a desk job. (By the way, if you’re presently seeking the next animated masterpiece, don’t watch You’re Under Arrest. This show is best for those who wish to enjoy some light comedy without being bombarded by fanservice.) Everything was proceeding as normal until the series introduced a love triangle and showed Kobayakawa distancing herself from her partner Tsujimoto. Usually, more conflict increases the value of a show, but a show needs to know what kind of conflict is suitable for it.

In the case of a show like You’re Under Arrest, interpersonal conflict among friends and dark, internal struggles ruin the work. Instead of the lighthearted fun and likeable characters for which the viewers watch the show, we see Kobayakawa become steadily more detestable as passion draws her closer to a mechanic aged thirty-something and his daughter(a nice guy, but one should avoid unequal relationships in general). This causes extreme suffering for her long time love interest, Nakajima, and leads to her getting into a serious fight with Tsujimoto, even slapping her at one point.

Now, in a certain book on novel writing (The Art & Craft of Novel Writing by Oakley Hall, I think), the author commented on how he hated simple characters. They’re boring, uninteresting, and more like children than adults. How is an adult supposed to relate to them? No doubt, Kousuke Fujishima thought like this when he decided to introduce these difficulties: that these struggles would result in the story becoming more interesting. The case is rather that this stands as one of the dullest, saddest five episodes stretches in the history of anime. I felt that several of the episodes past the middles of the second season were weak, but these were downright depressing!

If one thinks about it, much of the “complexity” we see in adults derives from sin. Adults wish to improve their situation in life and feel envy toward those who are above them either in terms of their position or of wealth; they have difficulty remaining faithful to one person because they think that indulging their lusts would be more pleasurable; they constantly want more stuff; they do not trust God and so suffer from many phobias and constantly fear being injured. Shall I go on? All these things make for complex characters, and several good stories have been made where plot centers on the main character overcoming his defects; but who would not prefer to be simple?

The simple man considers his station in life sufficient unless a true need arises, he does not bear ill will toward his superiors, he treasures his relationships, and fears nothing. If there is anything in his character which strikes others as an idiosyncrasy, he does not consider it as a cause for pride. Again, who would not rather be this person? Ah, such perfection is rarely achieved!

Which reminds me, one of the chief reasons a viewer likes or dislikes a story lies in whether he can identify with the characters. Interestingly, this identification occurs either because a character’s personality approximates the viewer’s or the viewer would like to become similar to that character. In the former case, we cheer the hero on, hoping for him to overcome all the obstacles. Sorrowing when he fails or rejoicing when he succeeds as if we ourselves rise or fall with him. In the latter, we see a model for us to attain. Seeing the greatness of this character, we are on fire to attain his virtues. The point of having the two kinds is so that one can see both the goal and how miserable it is to be away from the goal! The first spurs us by its beauty and the latter by revulsion.

To tie this back into You’re Under Arrest, Nakajima seems very much like myself. Even though he knows how to respond to matters well when it concerns his job, he procrastinates and is terribly unsure of himself when it comes to his human relationships. But, at the same time, he has a degree of reflection which usually prevents him from hurting other people–at least, by commission. Nakajima needs to learn more from Tsujimoto, who simply sizes up problems and does whatever she thinks is right. An example of simplicity very much worth following!

To wrap up with a more practical matter, I just need to decide whether I should go on to the third season. Considering that most of the characters are women, the first two seasons showed remarkable restraint when it came to fanservice, but this did increase over the course of the second. Does anyone have any opinions concerning how tolerable the third season is? Also, the episodes plots tended to be subpar in the second season. Does the third season offer an improvement in this area? Comments please! Especially if this article brought you some intellectual delight!

[…] In his analysis of You’re Under Arrest, Medieval Otaku relates the complexity of characters to human sinfulness. [Medieval Otaku] […]

LikeLike

[…] read: Simplicity and Identification in You’re Under Arrest and Kiba and Cheza’s Love as Symbolic of Jesus […]

LikeLike