I have become fascinated by a YouTube channel run by a user called Skallagrim. (His name is drawn from the father of the eponymous hero of Egil’s Saga, which fans of fantasy novels would surely enjoy reading.) In addition to the cool weapons and topics he presents, his honesty and cheerful personality make his videos enjoyable to watch. Recently, I stumbled across this video on how monotheism appears to non-believers. Christians do well to watch it because it very accurately describes the worldview of agnostics—or agnostic pagans as Skallagrim has described himself, though perhaps only semi-seriously.

After watching that, I found that I disagreed with so many things that I did not know where to start. My original thought was to write about why his impression of God is distorted from the way He really is. But then, the obvious question he might ask is why my view is any better than a Lutheran’s, Calvinist’s, Muslim’s, Jew’s, etc. In meditating before the tabernacle (and no, I did not go to the tabernacle in order to ask God how I should write this article, but the article kept surfacing in my mind), the understanding came to me that the essence of agnosticism, which inflicts the entire modern world, is the belief that one cannot know objective metaphysical truth. I italicize those words because agnostics obviously can believe in objective reality–and Skallagrim certainly does. However, trying to discern an objective order to the universe beyond what science can tell one is deemed a fool’s errand.

The pagans of ancient Mediterranean world believed the same thing. Relativism was as rampant in the ancient world as it is today. Disparate peoples compared their pagan religions to one another and found commonalities. They tolerated other pagan religions. The idea of fighting about religion was absurd to them. But, the progress of time caused pagans to be less religious, starting with the upper, educated classes. This culminated in religion being outward show for the majority by the first century before Christ.

What destroyed the credence pagan had in their religion? Obviously, it was not Christianity, which had not yet appeared. The cause lies in the advent of philosophy, particularly the Socratic philosophers. Socrates changed the world by seeking definitions of things in order to find out universal truths. No longer would mere dogma be satisfactory! Statements cannot be accepted on mere authority! Plato banned poets from his ideal city-state because he thought they perpetuated the lies found in mythology. Though Plato believed in a plurality of gods, he believed that the divine must be good and harmonious, not evil and discordant as we often see the Greek gods and goddesses act. Emphasizing this unity, Plato often refers only to one god. Aristotle further investigates the ideas found in Plato and posited a single “unmoved mover,” who must be God.

Basically, good philosophy–exemplified by Plato and Aristotle rather than the confusing mess offered by modern philosophies–renders the idea of a plurality of gods as untenable. Platonism and Aristotelianism point to a harmonious metaphysical realm which includes an unmoved mover who set everything else in motion and uncaused cause from whom all other causes derive. Isn’t it amazing that philosophy contains the similar truths found in the Catholic faith? So much so that Christianity has been called “Platonism for the masses”? St. Augustine describes a Platonic philosopher named Victorinus who believed in Christianity upon reading the Scriptures because of the way they connected with his philosophy. Yet, he hesitated to be baptized. When he told the Bishop Simplicianus of Milan that he was a Christian, Simplicianus said that he would not believe him until he had entered Church and received the sacraments. Victorinus’ succinct comeback “do walls make Christians?” is still remembered today. However, he did decide to get baptized and become a full member of the Catholic Church.

Why is this melding of philosophy and Christianity possible? It is well known that St. Augustine uses Platonism well to make sense of Christian doctrine, while St. Thomas does the same in his Summa Theologica with Aristotle. The fact of the matter is that Truth is one and objective. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle–no doubt with God’s Will–discovered parts of the truth and created systems which facilitated the understanding of Christians. They also share one commonality with early Christians: their fellow citizens persecuted them. Socrates was executed, Plato was charged in the same way as his master but fined instead, and Aristotle needed to flee Athens lest, as he put it, Athens commit a second crime against philosophy.

So, I would wish modern pagans and agnostics to give objective metaphysical truth a chance–to thoroughly test the metaphysical skepticism preached by analytical philosophy and Logical Posivitism by starting at the beginning of that non-authoritarian school known as philosophy. Read Plato and Aristotle. If Aristotle is too dry, read his most eloquent disciple, Cicero. See whether you’re convinced of their faith in objective metaphysical truth. (I might also add that one should read St. Thomas Aquinas, as he is more Aristotelian than Aristotle and the Churchmen of his time accused him of relying too much on philosophy.) See how modern philosophers challenge the Socratic Schools. Read modern defenders of older philosophical traditions like Peter Kreeft, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Mortimer Jerome Adler.

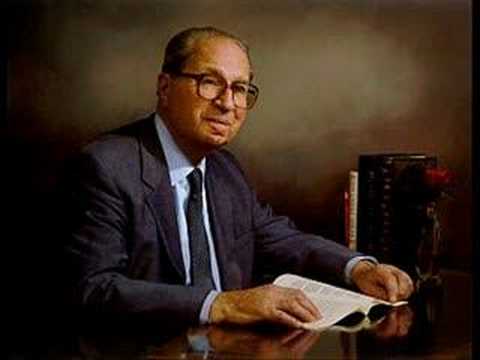

Despite being a Jew for most of his life, Mortimer J. Adler was one of America’s most popular Thomists.

The reason I recommend philosophy so much is because it arms one with the tools to discern good theology from bad. It is difficult to determine which religious truths don’t hold water, but having the tool of philosophy makes it much easier. So, do not seek religion for religion’s sake, but examine religions for the sake of the Truth. As I believe Jesus Christ is the Truth itself, seeing you seek Him will only draw Him faster to you: for all our striving, we do not find the Truth, but the Truth finds us–if only we care.

Great post! But To be fair, Augustine found Plato first and then when he found parts lacking turned to christianity. His thought was essentially that Platonism readied his mind to accept god.

LikeLike

That’s basically how I think Plato helped prepare the entire European world for Christianity. Of course, conversion is a matter of grace, but good philosophy cannot but aid one in understanding.

LikeLike

As I read this post, I thought about relativism. If truth were actually relative, I feel like that would be denying the existence of truth, which does not make sense at all (I feel like my head would enter a black hole if I tried to think about too deeply). Objective metaphysical truth…knowledge, meaning, the universe….Everything that we can encounter in the world…I feel like they can lead us to the objective truth that tries to reveal itself to us everyday. Ah, searching for the truth is tough, but I guess we’ll have to do it step by step, and do our best in it while having fun. 🙂

LikeLike

Exactly. Obviously, there exist things that are relative, but that pertains to differences in various species or personalities. Truth must indeed be unchanging for truth to exist at all.

The interesting thing about the world is that it was all created by God, and each living thing has perfections which exist in their highest forms in God. So, the creation is a guide to understanding the Creator. Of course, modern man has mentally divorced the Creator from His creation, which makes it even harder for them to perceive Him.

LikeLike

The thing is though, pagans weren’t really religious in the way we get them. It’s like Shinto; the religion was the expression of the national or local character and not subject to truth claims at all. Greeks didn’t care about other gods not because they were relativists, but because the other gods were foreign. It wasn’t being agnostic or not believing in objective metaphysical reality-it would be like trying to accuse people of not liking baseball or the fourth of july for those reasons.It waned because the structures of society also waned.

A book that really opened my eyes to old greek religion was Fustel De Coulanges’s the Ancient City. It really got into depth about how religion was woven into family, city, and nation.

LikeLike

It’s true. There is an element of nationalism in the way pagans have worshiped their gods. We see this especially in Cicero, who is probably the figure from whom Marx got the idea that religion’s purpose was to keep the proletariat in line. In the case of Japan, it is “the land of the gods,” so a Japanese converting to Christianity or a non-Christian religion can somehow make him appear less Japanese. On the other hand, some Japanese historians admire the Catholic martyrs of Japan, because they showed the courage considered natural to the Japanese spirit. Perhaps one day they shall be able to believe, as Tertullian wrote, “Anima naturaliter Christiana.”

But, there seems to be a progression in the way pagans thought about their religion. Hesiod of the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. certainly believed in the gods. I think that Socrates and most of his contemporaries did in the 5th, though his trial proves that there were political implications in believing or not believing in the gods. But sure, by the first century B.C. religion was primarily cultural and done to show that one fit into the society.

But, I do think that philosophy was integral to the waning of paganism. After all, the waning of the structures which kept paganism alive had no doubt to do with the change of mind which occurred in the ancient world. When one sees that societal customs are empty of meaning, they are not followed with as much fervor. We see the same with laws and customs in our country which were given meaning by Christianity. This coincides with the rise of modern philosophies which deny metaphysical reality, like Logical Positivism.

I’ll have to pick up The Ancient City at some point. It sounds like a great book.

LikeLike

I agree, but I want to point out a different tack. I’m not a relativist, but if I wish, I can (having done so in order to make a point a few times) deconstruct reality, bringing all truths into question. If I may quote C. S. Lewis for a moment: “Five senses; an incurably abstract intellect; a haphazardly selective memory; a set of preconceptions and assumptions so numerous that I can never examine more than a minority of them- never become even conscious of them all. How much of total reality can such an apparatus let through?”

It is true that there are logical streams of reasoning and ways of mapping what is true and what is not, but all are based on assumptions. It is easy to follow and credit the reasoning of someone who shares assumptions with us, but when the assumptions made are different, then the reasoning ceases to convince.

All that to say, your advice is excellent for some, but will carry no weight with others. In lieu of that, I believe that the way one lives, and the light of God shining through, has a great impact when reason fails.

LikeLike

The light of faith is certainly brighter than that of philosophy, and we shall only ever know a small part of the total reality. But, I’m not sure that all streams of reasoning are based on assumptions. Certainly, there are: the most common one being that our senses give us an accurate picture of reality–barring illusions like mirages, hallucinations produced by illness, and the occasions where people badly interpret sensory information. But denying the validity of certain assumptions, especially the senses, can lead us nowhere.

As for examples of reasoning which need no assumptions, the principle of non-contradiction and mathematical logic are excellent examples in addition to some other elementary rules of logic.

But, the assumptions one sees in various philosophies can be challenged, and it is possible to change people’s minds. Though, experience tells us that such changes are difficult and rare, which is another reason why grace is more important for religious conversion.

Thanks for your incisive comment!

LikeLike

I tend to think, for purposes of argument, that even mathematics can be called into question if one prods the assumption that our minds and perceptions are reliable at all. Existence and reality themselves can be called into question if the boundaries are pushed. As far as I can see, though, there is only one functional purpose to asking such (otherwise pointless) questions: it levels the playing field and, if well understood, teaches us to approach debate with humility. Many a time I have been confronted with someone who thinks (rightly) that my beliefs are based on assumptions but fails to see that theirs are as well. Not all of them have to see the universe deconstructed before they get the point, but sometimes they do.

That given, it is good to return to reality and embrace assumptions that put us back on a practical footing. I can argue against the existence of my desk, but when I am done, I will still set my cup of coffee on it. …mmm… coffee. I certainly hope coffee is real. 😉

It is possible for people’s minds to be changed, and whatever the means, I think grace is always involved. 🙂

And thank you for the engaging post! I enjoy niggling questions from time to time.

LikeLike

Those are good points to keep in mind. It is amazing how the principles others work under might be radically different from one’s own.

As you say, extreme skepticism is useful in reminding us of how little we know–it’s sort of like apophatic theology in that regard. But, no one could go through life as if nothing was certain. In the same way, we could not relate well to God if all we claimed to know about Him was that He exists.

LikeLike

“But, no one could go through life as if nothing was certain.” Exactly. Assumptions are necessary for every thought and action we take.

In the end, it all comes down to a choice. What assumptions do we choose to make, what evidence to we choose to trust, how do we choose to read that evidence? I’ve chosen Christ (at least from my perspective, He may see it differently), and I’m sure many people will analyze me and try to tell me the reasons I chose Him, but I did it with my eyes as open as I could get them, knowing I could not prove that He is Lord. Nevertheless, I believe He is, I believe I have evidence to support His divinity, and I have yet to see any evidence brought against that belief that holds water for two seconds.

LikeLike

There isn’t anything wrong with pagan gods, kami and the like, except that even if they do exist, their existence by itself does not answer metaphysical and ontological questions, as they too would be made from something and come from somewhere else.

In this sense, the Greek philosophers do share something with Christian philosophers in their search for singular and universal principles. On the other hand, the Greek philosophy put effort into reducing redundant concepts to simple truths. Just like it opposed multiple pagan gods, it would likely oppose a God setting the acceptable price of a slave at 30 silver pieces. The hundreds of pages the Bible devotes to handing out absolute judgments regarding things trivial or transient would not go down well with the philosophers, I believe, as that can be regarded as a similar kind of redundancy.

LikeLike

I tend to agree with your first statement, as far as the fact that I do not believe the existence of a single creative God discounts the existence of kami and the like.

However, I think you may have a simplistic view, and perhaps even a misunderstanding, of these “absolute judgements regarding things trivial or transient.” I should be careful, here, and say that a lot of people, Christian and otherwise, might disagree with what I am about to say. 🙂

I think that the Bible does many things, and one of those things is to track the training and preparation of humanity for salvation. The Levitical laws are a good example. They are given to a certain people at a certain time in order to shape and protect them. If you take a hard look at the history, and the cultures surrounding the Israelites, books like Leviticus take on a very different character. The laws regarding slavery came to a people in a time where slavery was ubiquitous, and most likely people would fail to understand (or obey) a command to cease it altogether. Instead, they get laws regulating it, limiting it, affirming the humanity of slaves and giving them a recourse to gain freedom. There are laws, there, intended to protect women and the poor, to guard from disease, etc.

I think that when the Christ came to fulfill the law, he did that by finishing the growing-up process of the law. God throws out laws several times in the Bible, showing that they are tools, not absolutes, and I think Christ supports this same idea.

I think you are probably right, in that the Greek Philosophers might well have regarded the Old Testament Jehovah as another god of the kind they discounted, but I also think that if they saw the bible in its entirety, they would be able to see the pattern, the work of meeting humanity where it is and dragging it, sometimes kicking and screaming, to a point where it could receive the Savior. I think, to some of them at least, it would make sense, as it makes sense to me.

This is a complicated thing, though, and many might disagree with me. I’m satisfied if I can simply give another angle for thought. 🙂

LikeLike

I understand your thoughts perfectly! However, as a non-believer, I see the point your raise as an important Bible-dilemma. If there is no need to see the decrees of the Bible as literally absolute, and we accept that they require interpretation or that they change over time, then most forms of religious authority are undone. Yet if we do not accept that, weirdness ensues. I brought up slavery because both old testament God and Christ were both alright with it (Christ at one point praises a slave-master for his unmatched faith) and yet the contemporary men revile it and perceive the abolishment of slavery as a great moral achievement.

LikeLike

I see that it is a dilemma for some, but I have never found it so in my walk. I find that God’s authority, that I see running through the Bible, is actually affirmed, something I can trust, as I trust a Being that understands humanity better than I do. The principles that all the laws are intended to point to, do not change at all. When Jesus lays out the principles and ways of God, they echo back through the Old Testament, the people are ready to hear them because they have been, sometimes unwittingly, acting on them for generations. Those who cling to the laws without understanding their purpose, Jesus treats as his enemies. The Ten Commandments (most of which make sense to most people, regardless of worldview) are the fundamental laws, to which Jesus adds context. He is not teaching us how to become good people under a law. He is preparing us to never need laws again. The tools can be discarded when the work is finished. Until then, the tools are very important to the work, so long as we recognize that they are tools, and not the end-all.

Mm, but in Jesus’s time slavery was still ubiquitous, and no one, or practically no one, would have understood why that was problematic. Also, the form slavery took (at least in the Roman Empire) was very different from the form it takes today, or took during colonialism and the history of the U.S.

Another interesting detail is that the price of Jesus’s life was thirty pieces of silver.

LikeLike

Yeah, it’s not a problem for individuals willing to make their own interpretations and follow them. It does become a problem when confronting the views of many different Christians, especially in the context of Christianity as an organized religion. There is a hierarchy out there claiming religious authority, and what does an individual do when their interpretations differ from the accepted norm? The fragmentation of Christianity into various denominations is a direct result of this dilemma.

LikeLike

Yes, that is absolutely true. There are even multiple hierarchies claiming authority. This fragmentation grieves and frustrates me.

I call myself a “non-denominational Christian.” To most people, that seems to mean “freaky-evangelical-whackado.” 😉

To me, what it means, is that I see value and commonality in the fragmented pieces of Christianity and long for reconciliation. I don’t think we all have to agree on everything, and I think there’s a heck of a lot we could learn from each other. There are efforts in many quarters to work towards this reconciliation, but the ever-deadly sin of Pride is always trying to tear those bridges down.

By the way, you are a pleasure to talk to. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks! What can I say, other than that I wholeheartedly applaud your approach?

I’m catholic by upbringing, Buddhist by philosophy. I don’t know which of God’s names (if any) is appropriate – those brought up in Christian families are highly likely to go through life calling Him Christ, those with Muslim roots will call Him Allah and so on – but I do know that all great religions that serve as the foundations of their respective societies are built upon love, goodness and justice. So it brings me great joy whenever two people choose to see the similarities first, differences second.

Christ did mention He would bring with Him inevitable division, but I cannot think He desired that state of division to last eternally within human hearts.

LikeLike

Of all the “mainstream” religions, Buddhism has the most resonance with me outside of Christianity.

Yes, I like it, too, when we are able to see commonalities and are able to discuss differences rather than rage over them.

Division does create choice, which is important, I think, but I do not think all these petty divisions serve a good purpose or are meant to last.

LikeLike

The jump between deism and theism is huge. I remember when an atheist told me that I had converted him to deism. I said to myself, “Excellent. He believes that God exists but doesn’t care about him. This is far short of what I hoped!” And I suppose that philosophy cannot argue well for a theistic God.

I am reminded of the example of Cicero–not regarded as a very logical philosopher, but possessed of great commonsense–saying that a workman cares about his work. If a workman cares about what he fashions, how could God not care about His creation? Man is the crowning achievement of God’s work; therefore, God must take greater pains about man than any other part of his creation. If that is the case, then why not interfere in matters which seem small?

Of course, the above argument relies on several assumptions. Though it seems to be a sound argument, I am sure that other philosophers would find problems with the premise of comparing God to a workman among other things.

LikeLike

Yes, the main issue is the view of God-as-person, which was partly what the philosophers wanted to avert, disappointed with the pagan gods. As far as I understand, the Christian God is at once a Something as well as a Someone, which is one of the complexities of the faith.

LikeLike

[…] studied swordsmanship for a long time. I disagree with him on religious issues–as you saw here; but his videos on swords, fencing, guns, gun rights, and various rambles make for informative […]

LikeLike